Traducción de este artículo en ingles

“Salvemos la raza humana, acabemos con el imperio”

En el curso de sus 14 años como Presidente de Venezuela, Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías se convirtió en una figura muy admirada entre la izquierda internacional. Aunque cualquier liderazgo revolucionario real y palpable siempre atraerá las sospechas de los socialistas de tertulia occidentales (y ciertamente Chávez tuvo su buena dosis de detractores), este grandioso personaje conquistó los corazones con su inmenso amor por el pueblo venezolano y su voluntad de defender alto y claro los ideales socialistas en un mundo post-soviético del fin de la historia donde pocos tuvieron el coraje de exponer tal punto de vista.

Nadie podría negar el papel que Chávez ha tenido como líder latinoamericano de la reacción contra el dogma neoliberal; tampoco se podría negar la naturaleza progresista y a favor de los pobres de los programas sociales de Venezuela. Bajo el liderazgo de Chávez, la riqueza petrolera de Venezuela (acompañada de los préstamos sin intereses chinos) se ha empleado de un modo excelente. Con la ayuda de los conocimientos expertos cubanos, el analfabetismo ha pasado a ser un mal recuerdo en Venezuela. El acceso a la educación ha aumentado drásticamente a todos los niveles, y se considera un componente fundamental de la creación de la democracia. Son famosas las palabras de Chávez, cuando sostuvo que “si queremos acabar con la pobreza, démosle poder a los pobres. ¡El conocimiento y la conciencia son el principal poder!”

Una vez más, con la ayuda de Cuba, el programa Barrio Adentro acercaba una sanidad de gran calidad a las comunidades más pobres de Venezuela, la mayoría de las cuales no había tenido acceso de ningún tipo a asistencia sanitaria profesional. Muy a pesar de las multinacionales occidentales, un gran número de empresas han sido nacionalizadas y se han llevado a cabo numerosos experimentos con la gestión de los trabajadores y la propiedad colectiva. Se han creado consejos comunalesde base por todo el país para atraer a las masas y crear una democracia más significativa. El proceso político puesto en marcha por Chávez es un programa orientado al socialismo que da prioridad a las necesidades de millones de personas ordinarias: los habitantes de los barrios marginales, los trabajadores, los campesinos, los desempleados, los indígenas, los africanos, los excluidos. Mientras tanto, el gobierno de Chávez celebraba elecciones como si fuesen a pasarse de moda. Este profundo proceso en Venezuela es tan emocionante que incluso ha conseguido ganarse el apoyo de secciones de la izquierda liberal occidental, por lo general tan clara en su rechazo total a los estados antiimperialistas y socialistas, desde A(rgentina) hasta Z(imbabwe).

Pero si hay un aspecto del legado de Hugo Chávez que hace sentir incómoda a la mayoría de la izquierda occidental (y que enfurece a las clases gobernantes occidentales) es el inquebrantable antiimperialismo de Chávez, su tenaz insistencia en la unidad a toda costa contra el principal enemigo. A nadie le cuesta alabar un hermoso programa de alfabetización, pero qué incomodo es ver a Chávez alinearse con lo que la caverna mediática del planeta ha etiquetado hace tiempo como “brutales dictaduras” en Iràn, Irak, Siria, Zimbabue, Cuba, Libia, Bielorrusia, Vietnam y Corea del Norte: “¿Cómo se le ocurre a Chávez? ¿Por qué tiene que llevarse tan bien con Rusia y China, los abusadores en serie de derechos humanos?“ Podemos descubrir este tipo de juicio en muchos de los obituarios a Chávez emanando de la izquierda occidental.

Por ejemplo, la indomable Organización ‘socialista’ internacional se quejaba de que “el legado internacional del presidente venezolano … se ha visto empañado por su atroz apoyo a Gadafi, Assad, Ahmadinejad y al estado chino”. A Owen Jones, ganador en 2013 de Britain’s Got Left-Liberal Talent, le preocupaban las “desagradables asociaciones extranjeras de Chávez. Aunque sus aliados más cercanos fueron sus compañeros de centro-izquierda elegidos democráticamente en Latinoamérica, también apoyó a brutales dictadores en Irán, Libia y Siria. Esto ha mancillado sin duda su reputación” (debería señalar de paso que el aliado más cercano de Chávez era Cuba, que suponemos que Jones no considera “democráticamente elegido” ¡y que se aparta mucho del centro-izquierda!).

Esta pauta – celebrar la política nacional de Venezuela mientras se denuncia su postura internacional – es un útil recordatorio de los límites de la democracia social occidental y claramente de todo el concepto de “libertad de expresión” en las sociedades capitalistas. Básicamente, se acepta un punto de vista ‘alternativo’ – y puede que hasta se le dé voz en los medios de comunicación liberales – en la medida en que se mantenga en límites bien definidos, dentro de lo razonable. El estado británico está dispuesto a tolerar un punto de vista minoritario que fomente una versión menos perturbada del capitalismo, especialmente si es en un país que no tiene demasiada conexión con los intereses económicos británicos. Lo que las clases dominantes occidentales nunca tolerarán – y por tanto lo que la izquierda socialdemócrata no promocionará – es una unidad antiimperialista global; hablamos de un apoyo inequívoco y coherente a todos los estados y movimientos que luchan contra el imperialismo. Dicha unidad es precisamente lo que presenta una amenaza existencial contra el imperialismo; es precisamente lo que Project for a New American Century (PNAC, Proyecto para un nuevo siglo americano) busca destruir; es precisamente lo que las inagotables estrategias de divide y vencerás buscan subvertir; es, en resumen, la única esperanza de poner fin a la dominación imperialista y crear un mundo donde los pueblos puedan desarrollarse en paz y seguridad. Como el propio Chávez afirmó: “Salvemos la raza humana – acabemos con el imperio”.

Chávez apoyó sin fisuras al movimiento global hacia la multipolaridad; a la creciente coordinación entre la familia progresista de naciones. Apoyó los profundos vínculos económicos, políticos y culturales entre estos estados que desafían la hegemonía occidental. Este aspecto de Chávez es absolutamente central para su legado político, y es lo que las clases dominantes occidentales más desprecian de él (en sus ojos había “heredado el manto de Fidel Castro como principal fastidio de Washington en Latinoamérica”). Lo que pretendo mostrar con este artículo es que, en lugar de meter bajo la alfombra el internacionalismo revolucionario de Chávez, o verlo como una mancha en su reputación progresista, este legado antiimperialista tiene que explorarse, entenderse, defenderse y construirse sobre él.

“No hay fronteras en esta lucha a muerte. No podemos ser indiferentes a lo que sucede en cualquier parte del mundo, ya que una victoria sobre el imperialismo de cualquier país es nuestra victoria; así como la derrota de cualquier país es la derrota de todos nosotros” (Ernesto Che Guevara).

La construcción del frente antiimperialista mundial

El mundo actual puede resultar implacable, especialmente para aquellos países con ideas ‘extravagantes’ sobre hacerse con el control de sus recursos naturales, la redistribución de la riqueza, la redistribución de la tierra, la puesta en práctica de una política exterior independiente y todo ese tipo de cosas. Los países de América Latina que, en el siglo XX, intentaron ejercer su independencia y soberanía fueron castigados por sus “pecados” con golpes de Estado brutales y despiadadas dictaduras (Argentina, Brasil, Chile). La minúscula Cuba ha sido sometida a medio siglo de bloqueo económico implacable, desestabilización política, aislamiento diplomático y unos cuantos cientos de intentos de asesinato. Cuando Zimbabue transfirió tierras de los colonos blancos ricos a los trabajadores nativos, negros y pobres, las clases gobernantes de Gran Bretaña y EE.UU. dejaron bien patente su descontento poniendo en marcha una campaña feroz de desprestigio contra el ZANU-PF y contra Robert Mugabe, así como imponiendo sanciones, y canalizando grandes sumas de dinero al opositor Movimiento para el Cambio Democrático. Cuando el presidente de Ucrania, Viktor Yanukovich rechazó el paquete de préstamos de la UE, con toda la bateria de consecuencias desagradables que dicho paquete conllevaba, y optó en su lugar por la ayuda económica rusa, éste fue inmediatamente barrido del poder por una “revolución” apoyada por Occidente. Los intentos de Vietnam, Corea, Irak, Yugoslavia, Afganistán, Granada, Nicaragua, Libia, y otros países, para forjarse un camino independiente han tenido como respuesta guerras imperialistas sin cuartel.

Sólo hay dos opciones viables para sobrevivir en un mundo tan hostil: capitular, o unirse y luchar.

Hugo Chávez veía el mundo de una forma muy lucida, casi visionaria; ello gracias a su profundo conocimiento de la historia mundial, a haber sido capaz de identificar el imperialismo liderado por Estados Unidos como el principal obstáculo para la paz y el desarrollo, y a sus propias experiencias a la hora de tratar de ejercer la soberanía y construir el socialismo en Venezuela (en medio de intentos de desestabilización y de golpes de Estado respaldados por la CIA). Chávez veía a Venezuela como parte de un movimiento global que desafiaba medio milenio de colonialismo, imperialismo y racismo; un movimiento global que incluía a China, Brasil, Rusia, Zimbabue, Libia, Siria, Sudáfrica, Cuba, Bielorrusia, Vietnam, Irán, Ecuador, Bolivia, Corea del Norte, Nicaragua, Argentina y algunos más. Chávez era consciente de que el enemigo utiliza todas las artimañas existentes para socavar a aquellos países que se niegan a alinearse con el Consenso de Washington, y comprendió la necesidad urgente de una unidad muy amplia con el fin de resistir este ataque. Esta interpretación llevó a Chávez a ser totalmente coherente en su lucha contra el imperialismo. Si la unión hace la fuerza, entonces uno no puede quedarse de brazos cruzados viendo como el imperio va derribando uno a uno a nuestros aliados. Como él mismo dijo durante una visita a Sudáfrica en el 2008:

“No se puede perder ni un día, ni un segundo, en esa tarea de unirnos los países del Tercer Mundo, del Sur”

De ahí que las sólidas relaciones que Chávez y su equipo construyeron con todos los estados socialistas y antiimperialistas no fueran ni anómalas, ni resultado de algún desafortunado accidente, ni de error de juicio, sino el resultado de una postura ideológica y estratégica clara para el chavismo.

Siria

“La civilización árabe y la nuestra Latinoamericana están llamadas en este siglo que comenzó a cumplir un papel fundamental en la liberación y salvación del mundo contra el imperialismo, contra la hegemonía capitalista y neoliberal que está amenazando la supervivencia de la especie humana. Siria y Venezuela están en la vanguardia de esta lucha.” (Hugo Chávez, 2010 , en el transcurso de la visita de Bashar Al-Assad a Caracas).

Al inicio de su presidencia, Chávez identificó a Siria como un aliado clave – uno de los pocos países en el mundo árabe que habían mantenido siempre una posición firme contra el imperialismo y el sionismo (recordemos que Chávez fue un firme defensor de Palestina y enemigo de Israel).

Al inicio de su presidencia, Chávez identificó a Siria como un aliado clave – uno de los pocos países en el mundo árabe que habían mantenido siempre una posición firme contra el imperialismo y el sionismo (recordemos que Chávez fue un firme defensor de Palestina y enemigo de Israel).

Siria, orgulloso miembro del famoso grupo ‘Más allá del Eje del Mal’ de John Bolton, era despreciada por occidente por su liderazgo en el apoyo a la resistencia palestina a lo largo de cuatro décadas, por su alianza con el movimiento de resistencia libanés Hezbolá (en 2006, el apoyo sirio resultó crucial para Hezbolá a la hora de derrotar a Israel en el sur del Líbano), y por su alianza con Irán.

En una visita a Damasco en agosto de 2006, Chávez, tras una larga reunión con el presidente sirio Bashar al-Assad, declaró: “Hemos decidido ser libres. Queremos colaborar en la construcción de un nuevo mundo donde los estados y la autodeterminación de los pueblos sean respetados… Tenemos la misma visión política y vamos a resistir juntos la agresión del imperialismo norteamericano”. En una nueva visita a Siria, en 2009, para elaborar un plan de cooperación económica, Chávez describió al pueblo sirio como “arquitecto de la resistencia” al imperialismo, y apeló a la unidad de los pueblos del Sur Global, proclamando: “debemos luchar para crear una conciencia libre de la doctrina imperialista… luchar para derrotar el atraso, la pobreza, la miseria (…) para convertir a nuestros países en verdaderas potencias a través de la conciencia de la gente”.

En el 2011, cuando Siria se vio amenazada por un golpe de Estado, bajo la doctrina de “cambio de régimen”, Chávez y su gobierno se apresuraron a declarar su lealtad al gobierno sirio. “Esta es una crisis planeada y provocada… Siria es una nación soberana. La causa de esta crisis es solo una: el mundo ha entrado en una nueva era imperial”. Es una locura”. Tras haber dejado muy clara su postura política, Venezuela pasó de las palabras a los hechos, enviando combustible diesel gratis a Siria en múltiples ocasiones para ayudarles a superar la escasez causada por las sanciones.

No hace falta decir que la postura abiertamente antiimperialista de Venezuela no fue apreciada por buena parte de la izquierda occidental. La web “Counterfire”, entre otros, castigó a Chávez en términos inequívocos por su apoyo abierto al gobierno sirio: “La declaración de apoyo del presidente venezolano Hugo Chávez al ‘líder socialista y hermano Bashar al Assad’, diciendo que es el objetivo de una operación imperialista para derrocar a su régimen y culpando a los EE.UU. por los disturbios en el país, es un insulto a los manifestantes sirios y a los mártires que perdieron la vida en el levantamiento contra el régimen autoritario sirio”. Según Al-Jazeera (portavoz de la monarquía Catarí – principal proveedor de armas y dinero a los grupos rebeldes de Siria), “Chávez y otros se desacreditaron y, probablemente, anularon la posibilidad de cualquier alianza duradera entre los revolucionarios árabes y fuerzas simpatizantes en América del Sur.”

Chávez no se dejó influir por estas críticas; defendió a Siria en su lucha contra la campaña para derrocar a su gobierno, en un momento en el que hacerlo resultaba altamente impopular. “¿Cómo podría no apoyar a Assad? Él es el líder del pueblo Sirio.”

En el transcurso de tres años, la verdadera naturaleza de la crisis Siria se ha hecho cada vez más evidente. Al mismo tiempo, el mito de la oposición democrática-socialista-feminista-pacífica-secular se ha ido desvaneciendo para dejar paso a una realidad bastante menos de color de rosa: la de sectas fundamentalistas asesinas (armadas hasta los dientes por Arabia Saudita, Cátar y Turquía, con la aprobación tacita de Gran Bretaña y los EE.UU) que están arrasando el país. (Mi artículo ‘La Descriminalización de Bashar‘ aborda este tema en detalle). Ahora está claro para todos que el plan de Occidente era sacar a Siria del eje de la resistencia, pero no siempre ha sido el caso. Analizando la situación desde el punto de vista del antiimperialismo militante, Chávez fue capaz de entender el panorama global desde un principio, en un momento en que otros muchos se creyeron las campañas de mentiras y de demonización.

Libia

Hugo Chávez vio en el líder libio, Muammar Gaddafi, a un aliado importante en la lucha mundial contra el imperialismo: alguien que sacó a su país de la dependencia colonial, que construyó un avanzado sistema de bienestar social (con el índice más alto de desarrollo humano, la esperanza de vida más alta, la más baja mortandad infantil y la tasa de alfabetización más alta de África), y que apoyó sin fisuras a movimientos socialistas y antiimperialistas de todo el mundo, desde Irlanda hasta Sudáfrica, de Nicaragua a Palestina, de Dominica a Namibia. De hecho, Chávez visitó Libia en cinco ocasiones durante su presidencia. En Trípoli, durante la celebración del 40 aniversario de la revolución libia (2009), declaró que Venezuela y Libia “comparten el mismo destino, la misma batalla contra un mismo enemigo y vamos a ganarla”. A continuación, hizo un emotivo llamamiento a la unidad africana:

“El África es el África, y el África más nunca debe permitir que vengan países de más allá de los mares a imponer los sistemas políticos, económicos o sociales que el África y sus pueblos necesitan. África debe ser de los africanos y solo mediante la unidad África será libre y grande.”

Tan sólo unas semanas después, Gadafi llegó a Venezuela en su primer viaje a América del Sur. Durante la Cumbre África-América del Sur, celebrada en la Isla de Margarita, Chávez regaló a Gaddafi una réplica de la espada del héroe de la independencia de Venezuela, Simón Bolívar. Chávez declaro: “Gadafi es para Libia lo que Bolívar es para nosotros.” El objetivo común de Chávez y Gadafi fue el de de marcar el comienzo de una nueva era de cooperación a gran escala entre África y América Latina.

Tan sólo unas semanas después, Gadafi llegó a Venezuela en su primer viaje a América del Sur. Durante la Cumbre África-América del Sur, celebrada en la Isla de Margarita, Chávez regaló a Gaddafi una réplica de la espada del héroe de la independencia de Venezuela, Simón Bolívar. Chávez declaro: “Gadafi es para Libia lo que Bolívar es para nosotros.” El objetivo común de Chávez y Gadafi fue el de de marcar el comienzo de una nueva era de cooperación a gran escala entre África y América Latina.

Al igual que en Siria, Chávez entendió desde el principio lo que el ‘levantamiento’ en Libia significaba. Mientras los iluminados de la izquierda británica, como Gilbert Achcar, pedían a gritos una zona de exclusión aérea para lograr deshacerse de Gadafi, Chávez salió en defensa de su amigo y compañero: “Se está tejiendo una campaña de mentiras con respecto a Libia. Yo no voy a condenar a Gadafi. Sería un cobarde si condenara a alguien que ha sido mi amigo.”

Venezuela encabezó los llamamientos por una solución pacífica a la crisis, ofreciendo sus servicios en varias ocasiones para mediar entre el gobierno libio y los rebeldes. “Vamos a tratar de ayudar, de interceder entre las partes. Un alto el fuego, sentados alrededor de una mesa. Ese es el camino en este tipo de conflictos.” Lamentablemente, los rebeldes y sus aliados de la OTAN no tenían el más mínimo interés en negociaciones.

Junto con sus aliados regionales, Cuba, Argentina, Bolivia, Nicaragua y Ecuador, Venezuela denunció sin ambigüedades el salvaje bombardeo de la OTAN. “Libia está bajo fuego imperial. Nada lo justifica”, dijo Chávez. “Bombardeo indiscriminado. ¿Quién le dio a esos países el derecho? Ni Estados Unidos, ni Francia, ni Inglaterra, ni ningún país tiene derecho a lanzar bombas… Desearía que estallase una revolución en los Estados Unidos. Vamos a ver lo que harían.” Chávez resumió de forma muy clara y sencilla lo que era la “post estrategia del consenso de Washington” adoptada por la OTAN, al declarar: “El imperio se está volviendo loco y es una amenaza real para la paz mundial, el imperialismo ha entrado en fase de locura extrema”. Y en agosto de 2011, cuando Trípoli fue sometida a base de bombardeos, Chávez predijo, en lo que sería una profecia, que “el drama de Libia no termina con la caída del gobierno de Gadafi. La tragedia de Libia apenas está comenzando.”

Libia fue otro de los temas en los que el sólido antiimperialismo de Chávez chocaba frontalmente con el liberalismo primer-mundista de la izquierda occidental. Mientras que Alex Callinicos , principal teórico del vergonzosamente mal llamado “Partido Socialista de los Trabajadores” (Reino Unido), llamaba a sus seguidores a “_unirse a las celebraciones de los Libios por la desaparición del tirano*”, la noticia del asesinato de Gadafi orquestado por la OTAN afectó mucho a Chávez: *”Lamentablemente, se ha confirmado la muerte de Gadafi. Fue asesinado… le recordare toda mi vida como un gran luchador, un revolucionario y un mártir.”*

Si, hay un patrón de comportamiento. La izquierda occidental, casi invariablemente, ha optado por apoyar las campañas de demonización contra los Estados socialistas y antiimperialistas, orquestadas por la prensa de extrema derecha. Por su lado Chávez, incansable, vio más allá de la propaganda y se mantuvo fiel a su sueño de unidad mundial contra el imperio. En un mundo de cobardía e inconstancia, se alzo y dijo: “Yo no soy un cobarde, yo no soy un veleta.“

Chávez partía de una postura de desconfianza instintiva hacia la propaganda proveniente de occidente. Nunca se dejo arrastrar por los relatos simplistas sobre ‘dictadores diabólicos’, como Blofeld, el personaje malvado de la serie James Bond. Su trayectoria y su experiencia política le habían enseñado que los medios de comunicación no son de fiar; que los imperialistas manipulan cada noticia para satisfacer sus propios intereses. Los medios de comunicación en Venezuela siguen estando principalmente en manos de las elites, que odiaban a Chávez, al que sometían a ataques racistas y clasistas, a la par que propagaban mentiras y calumnias sobre él. Así las cosas, para Chávez estaba muy claro que lo que se decía sobre los otros países del ‘Eje del Mal Prolongado’ eran, con toda probabilidad, estupideces.

Mientras tanto, ¿qué países ayudaron a Venezuela, apoyando sus políticas, apoyando la integración regional de América Latina? ¿Qué países apoyaron los movimientos de liberación en todo el mundo? ¿Qué países apoyaban la liberación de Palestina -por ejemplo, suministrando armas para la defensa de Gaza? ¿Qué países se enfrentaron a EE.UU., Gran Bretaña, Francia e Israel?

Irán

Irán es otro de los países que viene siendo sometido regularmente a las campañas occidentales de calumnia y demonización, pero también es otro país con el que Hugo Chávez creó fuertes vínculos de amistad, con el consiguiente disgusto del imperialismo occidental. En un artículo fascinante por su estupidez publicado en marzo del 2007, el veterano republicano Bailey Hutchison vociferaba lo siguiente: “En su lucha contra el ‘imperialismo’ estadounidense, Chávez ha encontrado un aliado muy útil en el más importante patrocinador mundial del terrorismo – el gobierno de Irán. Es uno de los pocos líderes que se atreve a apoyar públicamente el programa de armas nucleares de Irán. Y los ulemas iraníes han recompensado la amistad de Chávez con lucrativos contratos, incluida la transferencia de tecnología y de profesionales iraníes a Venezuela. El mes pasado, el Sr. Chávez y el presidente iraní Mahmoud Ahmadinejad anunciaron planes para crear un fondo común por valor de dos mil millones de dólares, parte de los cuales será utilizado como un ‘mecanismo de liberación’ contra los aliados norteamericanos… Si no se ponen límites a esto, los Sres. Ahmadinejad y Chávez podrían convertirse en el nuevo tándem Khrushchev- Castro del inicio de este siglo XXI, canalizando armas, dinero y propaganda a América Latina, y poniendo en peligro una región de democracias frágiles y economías volátiles.”

Chávez visitó Irán en numerosas ocasiones, y de igual forma recibió a su homólogo iraní, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, en Venezuela varias veces. A pesar de sus diferencias ideológicas y de tener concepciones filosóficas distintas, los dos líderes crearon una sólida alianza basada en la unidad anti-imperialista. “Nosotros sabemos que Irán es uno de los objetivos que el imperio yanqui tiene en el punto de mira hace mucho tiempo”, Chávez dijo. “Cuando nos reunimos los diablos se vuelven como locos.” Ahmadinejad describió a Chávez como a “un hermano y compañero de trinchera” y calificó a Irán y Venezuela como piezas fundamentales de un frente revolucionario “que se extiende hasta el este de Asia” desde América Latina. “Si hubo un dia en que mi hermano Chávez y yo, junto a otros pocos, estuvimos solos en el mundo, hoy contamos con una larga lista de mandos de la Revolución y gente de a pie resistiendo codo a codo.”

Chávez visitó Irán en numerosas ocasiones, y de igual forma recibió a su homólogo iraní, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, en Venezuela varias veces. A pesar de sus diferencias ideológicas y de tener concepciones filosóficas distintas, los dos líderes crearon una sólida alianza basada en la unidad anti-imperialista. “Nosotros sabemos que Irán es uno de los objetivos que el imperio yanqui tiene en el punto de mira hace mucho tiempo”, Chávez dijo. “Cuando nos reunimos los diablos se vuelven como locos.” Ahmadinejad describió a Chávez como a “un hermano y compañero de trinchera” y calificó a Irán y Venezuela como piezas fundamentales de un frente revolucionario “que se extiende hasta el este de Asia” desde América Latina. “Si hubo un dia en que mi hermano Chávez y yo, junto a otros pocos, estuvimos solos en el mundo, hoy contamos con una larga lista de mandos de la Revolución y gente de a pie resistiendo codo a codo.”

Uno de los resultados de las estrechas relaciones de amistad que establecieron los dos países fue que la cooperación, a nivel práctico, se incrementó. El comercio se multiplicó por 100 desde el 2001 (se estima que el comercio bilateral supera los 40 mil millones dólares), y los dos países se embarcaron en empresas conjuntas en varias áreas, incluyendo la energía, la agricultura, la vivienda y la infraestructura. La experiencia iraní en el ámbito de construcción fue aprovechada para construir miles de viviendas para los pobres de Venezuela.

Chávez defendió el derecho de Irán a desarrollar la energía nuclear y señaló con mucha agudeza que la cuestión nuclear estaba siendo utilizada por occidente para movilizar a la opinión pública en favor de una guerra, “de la misma forma que usaron la excusa de las armas de destrucción masiva para hacer lo que hicieron en Irak.” Chávez manifestó el firme apoyo de Venezuela a Irán con respecto a la amenaza de guerra contra ellos: “Deberí a aprovechar esta oportunidad para condenar esas amenazas militares que se están haciendo contra Irán. Sabemos que nunca serán capaces de ponerle límites a la revolución islámica de ninguna manera. Estaremos siempre juntos, no sólo resistiremos, sino que juntos saldremos victoriosos.”

Irak

Una de las prioridades de Hugo Chávez, en los primeros años de su presidencia, fue revitalizar la Organización de Países Exportadores de Petróleo (OPEP), a fin de asegurar un acuerdo que regulase la producción y aumentase los precios. Tras haber fijado una fecha para una cumbre de la OPEP que reuniese a todos sus miembros (se trataba de la segunda en la historia de la organización y la primera en 25 años), Chávez se embarcó en una gira para visitar los diez países de la OPEP con el fin de invitar personalmente a cada jefe de Estado. Este itinerario incluía necesariamente a Irak, miembro de la OPEP. La visita de Chávez a Irak, en agosto de 2000, produjo una oleada de controversia, indignación y ansiedad en todo el mundo occidental.

“Washington dijo que estaban en contra de mi visita a Bagdad, yo les dije que iba a ir de todas formas. Ellos argumentaron que había una zona de exclusión aérea y que no podría atravesarla sin riesgo de que me derribasen el avión. Pero fuimos a Bagdad de todos modos y hablamos con Saddam”. (Citado por Bart Jones en “La Historia de Hugo Chávez”).

De hecho, Chávez fue el primer jefe de Estado que visitó Irak tras la imposición de sanciones por la ONU en 1991. Para poder esquivar la prohibición de vuelos internacionales hacia Irak, Chávez y su equipo cruzaron desde Irán a Irak por tierra y después volaron a Bagdad en helicóptero. Allí fue recibido personalmente por Saddam Hussein, quien lo llevo a hacer una visita nocturna por Bagdad. En respuesta a las críticas de la “comunidad internacional”, Chávez declaró desafiante: “Lamentamos y denunciamos la injerencia en nuestros asuntos internos. Ni la aceptamos, ni la aceptaremos… Estamos muy contentos de estar en Bagdad, de oler el aroma de la historia y de caminar por las orillas del río Tigris.”

De hecho, Chávez fue el primer jefe de Estado que visitó Irak tras la imposición de sanciones por la ONU en 1991. Para poder esquivar la prohibición de vuelos internacionales hacia Irak, Chávez y su equipo cruzaron desde Irán a Irak por tierra y después volaron a Bagdad en helicóptero. Allí fue recibido personalmente por Saddam Hussein, quien lo llevo a hacer una visita nocturna por Bagdad. En respuesta a las críticas de la “comunidad internacional”, Chávez declaró desafiante: “Lamentamos y denunciamos la injerencia en nuestros asuntos internos. Ni la aceptamos, ni la aceptaremos… Estamos muy contentos de estar en Bagdad, de oler el aroma de la historia y de caminar por las orillas del río Tigris.”

Los dos dirigentes mantuvieron largas conversaciones, descritas por Chávez como fructíferas. “Descubrí que era un hombre educado, que comprendía todo aquello relacionado con la OPEP”. Chávez y sus colegas también aprovecharon la oportunidad para denunciar el régimen de sanciones internacionales responsable de las muertes de cientos de miles de niños iraquíes. El vice ministro de exteriores, Jorge Valero, declaró: “El presidente Chávez reafirma la posición venezolana de apoyar toda iniciativa que ponga fin a cualquier tipo de bloqueo o sanciones unilaterales a Irak o a cualquier otro país del mundo.”

Uno de los resultados más impactantes de los esfuerzos de Chávez fue que, apenas unas semanas después de su visita a Bagdad, y en el marco de la cumbre de la OPEP en Caracas, Irán e Irak celebraron las conversaciones al más alto nivel desde la trágica y terrible guerra que tuvo lugar entre los dos países (que duró de 1980-1988 y que tuvo como resultado al menos un millón de muertes). El Vicepresidente iraquí, Taha Yassin Ramadan, dijo que las conversaciones con el presidente iraní, Mohammad Khatami fueron “cordiales y francas. Hablamos de la cooperación entre los dos países y acordamos trabajar conjuntamente para la mejora de las relaciones entre los dos países.” Chávez comentó: “Estoy a su servicio para ayudarles … a la reactivación plena de las relaciones entre dos pueblos hermanos, dos países hermanos , que también son miembros de la OPEP, y que piden un impulso en la reunificación de todo el mundo árabe-islámico.”

El hecho de que Chávez estuviera dispuesto, y fuera capaz de facilitar este proceso, ya nos habla de su genialidad estratégica y de su visión a largo plazo. A pesar de ser plenamente consciente de la dolorosa enemistad entre Irán e Irak; a pesar de ser consciente de las dificultades que conllevaba el camino de la reconciliación, Chávez supo que aliviar la tensión entre estas dos grandes naciones significaba darle un impulso al frente anti-imperialista mundial. Los efectos secundarios podían conllevar la reconciliación entre Irak y Siria (Siria era un aliado muy próximo de Irán), entre Irak y Libia (quien había apoyado a Irán en la guerra Irán-Irak), entre Irán y el mundo árabe en general, y entre las diferentes facciones palestinas. Si este proceso de acercamiento hubiera logrado plasmarse, la región en su conjunto habría estado en una posición mucho más fuerte en su lucha contra el imperialismo y el sionismo. Se habría avanzado en la lucha palestina por la autodeterminación, y se podría haber evitado la desastrosa guerra de Irak, en la que más de un millón de iraquíes perdieron la vida. De hecho, la posibilidad de una unidad regional basada en la reconciliación entre Irán e Irak pudo haber sido uno de los factores que decidieron a EE.UU. y a Gran Bretaña a lanzar la invasión de Irak en el 2003.

Cuba

El estado más difamado en el hemisferio occidental, Cuba, ha sufrido durante años un bloqueo económico y diplomático impuesto de forma brutal. Hasta hace pocas décadas, la mayoría de los gobiernos latinoamericanos evitaban a Cuba por temor a molestar a sus amos al norte de la frontera. Sin embargo, la situación ha cambiado significativamente en los últimos 15 años, desde que Chávez emprendio la Revolución Bolivariana en Venezuela.

El estado más difamado en el hemisferio occidental, Cuba, ha sufrido durante años un bloqueo económico y diplomático impuesto de forma brutal. Hasta hace pocas décadas, la mayoría de los gobiernos latinoamericanos evitaban a Cuba por temor a molestar a sus amos al norte de la frontera. Sin embargo, la situación ha cambiado significativamente en los últimos 15 años, desde que Chávez emprendio la Revolución Bolivariana en Venezuela.

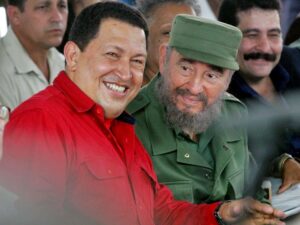

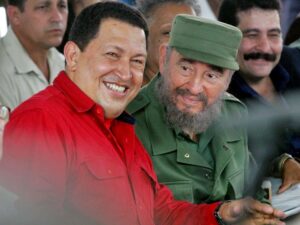

Chávez nunca ocultó su afecto por Cuba, ni su admiración por el socialismo cubano y su internacionalismo militante, ni su respeto por Fidel Castro en tanto que revolucionario.

“Fidel para mí es un padre, un compañero, un maestro de la estrategia perfecta.” Hugo Chávez, 2005.

Durante su visita a Cuba en 1999, Chávez, dirigiéndose a la audiencia de la Universidad de La Habana, dijo que “Venezuela está navegando hacia el mismo mar que el pueblo cubano, un mar de felicidad, de justicia social y de paz verdaderas… Aquí estamos, más alerta que nunca, Fidel y Hugo, luchando con dignidad y valor para defender los intereses de nuestros pueblos y haciendo realidad el pensamiento de Bolívar y de Martí. En nombre de Cuba y Venezuela, quiero hacer un llamamiento a la unidad de nuestros pueblos y de las revoluciones que encabezamos. Bolívar y Martí, un país unido!” (citado en Richard Gott ‘Hugo Chávez y la Revolución Bolivariana’). En una de las ocasiones en que respondía a la acusación de que Cuba era una “dictadura”, Chávez señaló que Cuba tiene formas de democracia mucho más profundas y amplias que los países que vierten las acusaciones. “Mucha gente me ha preguntado cómo puedo apoyar a Fidel si es un dictador. Pero Cuba no es una dictadura… es una democracia revolucionaria.”

En el 2000 se firmaron una serie de acuerdos de ayuda mutua, que actuaron como un balón de oxigeno para la economía de Cuba y resultaron cruciales para el éxito de los programas sociales de Venezuela. El programa de salud comunitaria Barrio Adentro llevo el conocimiento médico cubano a millones de pobres venezolanos. Según estimaciones oficiales, “ha salvado la vida a 1,5 millones de venezolanos. Y otros 1,5 millones se beneficiaron también (sin coste alguno) de la cirugía ocular de la Misión Milagro, otro programa cubano de atención sanitaria, creado en 2004, para proporcionar cuidados oftalmológicos gratuitos a la poblacion”.

En el 2000 se firmaron una serie de acuerdos de ayuda mutua, que actuaron como un balón de oxigeno para la economía de Cuba y resultaron cruciales para el éxito de los programas sociales de Venezuela. El programa de salud comunitaria Barrio Adentro llevo el conocimiento médico cubano a millones de pobres venezolanos. Según estimaciones oficiales, “ha salvado la vida a 1,5 millones de venezolanos. Y otros 1,5 millones se beneficiaron también (sin coste alguno) de la cirugía ocular de la Misión Milagro, otro programa cubano de atención sanitaria, creado en 2004, para proporcionar cuidados oftalmológicos gratuitos a la poblacion”.

Además: “Otros 53,000 venezolanos con enfermedades crónicas han recibido atención sanitaria gratuita en Cuba, gracias a un Acuerdo bilateral firmado entre las dos naciones latinoamericanas que refuerza los servicios sociales y mejora la calidad de vida de la población Venezolana.” Por otro lado, Cuba proporcionó también profesionales y apoyo técnico al programa de alfabetización de Venezuela, que ha resultado un rotundo éxito al eliminar el analfabetismo del país.

Venezuela paga por estos servicios cruciales para la nación con petróleo gratuito o fuertemente subvencionado, lo que ha significado un enorme impulso a la economía cubana. Venezuela también ha ayudado a Cuba con prestamos e inversiones por valor de miles de millones de dólares. Ello significa que ha roto con pleno conocimiento y orgullo el bloqueo económico de los Estados Unidos contra Cuba. En una larga entrevista concedida a Aleida Guevara, Chávez decia: “Antes, Venezuela no vendía petróleo a Cuba. ¿Por qué no? Por una orden de Washington, por el bloqueo, y la Ley Helms-Burton. A nosotros eso no nos importa nada, Cuba es nuestra nación hermana y le venderemos a Cuba.”

Chávez recibió incontables andanadas de críticas desde los Estados Unidos por su relación con Cuba. No hace falta decir que no le afectaron en lo más mínimo.

“Nunca me cansaré de manifestar mi reconocimiento al fantástico apoyo de Cuba, de subrayar mi gratitud en público, donde sea que me halle, con quien quiera que este, en el foro mundial al que se dé la ocasión de dirigirme, sin importarme cuantos rostros ardan de rabia porque me este refiriendo a Cuba en estos términos… [En la Cumbre de las Américas de Monterrey en el 2003] me dijeron que Bush ardía de rabia. Yo no le estaba mirando, pero luego me contaron que se había puesto rojo y se quedó inmóvil, inexpresivo sentado en su sillón. Yo había mencionado a Cuba tres veces.. Había agradecido al pueblo cubano y a Fidel su ayuda. No lamento nada… Eso es lo que Gaddafi me dijo cuando le conté por teléfono lo que había ocurrido en Monterrey. Me preguntó porqué Cuba no estuvo en una cumbre que es para la totalidad del continente Américano. ‘Ah bueno! Es porque Estados Unidos excluyó a Cuba.’ Me respondió, ‘Escucha Hugo, en una ocasión aquí, en África, los británicos trataron de impedir que Mugabe, el presidente de Zimbabue, asistiera a una reunión de la Unión europea sobre África. Nosotros dijimos que si Mugabe no venia, nadie vendría. América Latina debería hacer lo mismo.’” (Citado en Aleida Guevara Chávez, Venezuela y la Nueva América Latina)

La mera mención de los nombres de Castro, Gaddafi y Mugabe en un mismo párrafo basta para sacar una mueca de dolor a los socialdemócratas de la Izquierda liberal -tan desmesurado es su afán por ser aceptados; tal su esclavitud a la máquina de propaganda imperialista occidental. Chávez, al contrario, no permitió a los imperialistas influenciar su juicio ni un átomo. Simplemente seguía adelante con el trabajo de construir un frente anti-imperialista global por todos los medios necesarios. Como la embajadora de Argentina en el Reino Unido lo expresó durante una reciente conferencia de la Campaña de Solidaridad con Venezuela:

“Chávez nos enraizó al tronco de la unidad, con la base más amplia que se pueda dar: la unidad con cualquiera que tenga la mas mínima posibilidad de unir sus fuerzas contra el Imperialismo.”

Multipolaridad: desmontando el imperio

Con el declive de la hegemonía política y económica de los EE.UU., el ascenso de China, la progresiva emergencia de América Latina, y el resurgimiento de Rusia a partir del fin de la era Yeltsin, el mundo se mueve inexorablemente hacia un modelo ‘multipolar’– “un patrón de múltiples centros de poder, todos con una cierta capacidad para influenciar cuestiones internacionales, dando forma a un orden concertado“ (asi define Jenny Clegg la multipolaridad en su libro, China’s Global Strategy). China ha sido especialmente dinámica en la promoción de la multipolaridad como un medio realista de contener el imperialismo, al tiempo que se trabaja por un orden mundial democrático y estable en el que los países antiguamente oprimidos puedan desarrollarse en paz. Hugo Chávez fue un firme defensor de este concepto, y lo conectó al pensamiento del héroe de la independencia de Venezuela, Simón Bolívar:

“Bolívar concibió un ideal internacionalista. Habló de lo que hoy nosotros llamamos mundo multipolar. Propuso la reunificación de América del Sur y Centroamérica en lo que llamó la Gran Colombia, para posibilitar negociaciones sobre una base de igualdad con las otras tres cuartas partes del globo. Eso ya era una visión multipolar.” (Citado en Bart Jones The Hugo Chávez Story)

Integración regional

Chávez persiguió enérgicamente la integración regional dentro de Suramérica, Centroamérica y el Caribe como medio para crear una fuerza unida y progresista que pudiese conectar “con igualdad con las otras tres cuartas partes del mundo”. Los analistas antiimperialistas nicaragüenses Jorge Capelán y Toni Solo afirman que “en Latinoamérica, es imposible participar en la construcción de alternativas socialistas y anticapitalistas sin luchar al mismo tiempo por integrar la región política, económica e incluso culturalmente… Ese es el legado de Bolívar, como fue el legado de Martí, Sandino, Mariátegui, Gaitán, Che, Fidel Castro y muchos otros revolucionarios latinoamericanos desde la Independencia. Esto es así porque los poderes coloniales e imperialistas necesitaban dividir la región en pequeños países para explotar sus recursos y mano de obra. No es algo que se haya inventado Chávez, es una perspectiva antigua en la región.”

Se ha perseguido este proyecto a través de la creación de diversas organizaciones de integración regional, en particular ALBA (Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América ), CELAC (Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños) y UNASUR (Unión de Naciones Suramericanas), así como proporcionando apoyo a otras naciones latinoamericanas y caribeñas con visiones semejantes, por ejemplo, ofreciendo a los países más pobres de la región acceso al petróleo venezolano en condiciones preferenciales. En la era actual estamos siendo testigos del resurgir de una Latinoamérica que cada vez está más dominada por países progresistas y que está moviéndose con confianza hacia la integración y la solidaridad. El analista español Ignacio Ramonet comenta que “el ejemplo de Chávez se ha seguido, con diferentes matices, en otros países. En Brasil, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, entre otros, se han dado una serie de procesos que, hasta cierto punto, han avanzado por la ruta abierta por la Revolución bolivariana.”

Se ha perseguido este proyecto a través de la creación de diversas organizaciones de integración regional, en particular ALBA (Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América ), CELAC (Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños) y UNASUR (Unión de Naciones Suramericanas), así como proporcionando apoyo a otras naciones latinoamericanas y caribeñas con visiones semejantes, por ejemplo, ofreciendo a los países más pobres de la región acceso al petróleo venezolano en condiciones preferenciales. En la era actual estamos siendo testigos del resurgir de una Latinoamérica que cada vez está más dominada por países progresistas y que está moviéndose con confianza hacia la integración y la solidaridad. El analista español Ignacio Ramonet comenta que “el ejemplo de Chávez se ha seguido, con diferentes matices, en otros países. En Brasil, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, entre otros, se han dado una serie de procesos que, hasta cierto punto, han avanzado por la ruta abierta por la Revolución bolivariana.”

Con el liderazgo de Chávez y Lula en particular, Latinoamérica ha conseguido estar más cerca que nunca de la soberanía económica. En 2005, el plan de EEUU de una zona de libre comercio en las Américas (Área de Libre Comercio de las Américas (ALCA)) fue integralmente derrotada en la Cumbre de las Américas en Mar del Plata, Argentina. “Sin el liderazgo conjunto de Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, Lula da Silva y el fallecido presidente argentino Néstor Kirchner, esta derrota estratégica del imperialismo en Latinoamérica no habría sido posible.”

La amistad con China

Más allá de Latinoamérica, Chávez puso muchos esfuerzos en crear firmes lazos con las principales potencias emergentes del mundo, especialmente con China y Rusia – naciones que Fidel Castro describió como “los dos países llamados a liderar un nuevo mundo que permita la supervivencia humana, si el imperialismo no desata antes una guerra criminal de exterminio.”

Bart Jones escribió, “la mayor iniciativa internacional de Chávez fuera de América Latina estuvo enfocada hacia China… El hambriento mercado energético de China era el candidato ideal para los planes de Chávez de distanciarse, lo máximo posible, de la esfera de influencia de Estados Unidos y de promover un mundo multipolar. Chávez llegó a un acuerdo para enviar petróleo a China. Comenzó con un compromiso en el 2005 de suministrar treinta mil barriles al día. En el 2007 saltó a trescientos mil, con una última meta de medio millón de barriles al día para el 2009 o 2010. Esto era parte de un plan para incrementar, desde el 15 por ciento al 45 por ciento, la cantidad de crudo y otros productos petrolíferos que Venezuela enviaría a Asia.”

Chávez vio claramente que China era un socio crucial en la batalla por un Nuevo Mundo, y la visitó seis veces a lo largo de su mandato, estableciendo estrechos lazos económicos, diplomáticos y políticos. En su primer viaje, en 1999, expresó su admiración por el modelo económico chino de socialismo de mercado, declarando: “Asistimos al triunfo de la Revolución china.” El modelo chino, con el Estado controlando las posiciones de mando de la economía, mientras apoya una economía privada regulada para los sectores menos cruciales, ha desempeñado un papel importante en la conformación de la propia política económica de Venezuela en los últimos 15 años.

En el 2006, Chávez sulfuró a imperialistas y liberales de todo el planeta al describir la Revolución china como “uno de los mayores acontecimientos del siglo XX”, y al decir que el Socialismo chino es “un ejemplo para aquellos dirigentes y gobiernos occidentales que argumentan que el Capitalismo es la única alternativa.” Durante el mandato de Chávez, Venezuela se convirtió rápidamente en uno de los aliados clave de China en América Latina, y Chávez fue considerado como un “gran amigo del pueblo chino”.

Al aclamar la emergencia de China como gran potencia mundial, Chávez planteaba la diferencia fundamental entre el papel de China – que se ha desarrollado mediante su propia diligencia y perseverancia – y el de las potencias colonialistas/imperialistas, que construyeron su riqueza a partir del saqueo, el genocidio, el golpismo, el terror y la explotación. “China es grande, pero no es un Imperio. China no atropella a nadie, no ha invadido a nadie, no va por ahí lanzando bombas a diestro y siniestro.” El sucesor de Chávez, Nicolás Maduro, abundó en este punto: “Las relaciones internacionales de China parten de una base de igualdad, demostrando así que, en este comienzo del siglo XXI , es posible construir nuevas potencias mundiales sin la práctica imperialista de la colonización y la dominación.”

Al aclamar la emergencia de China como gran potencia mundial, Chávez planteaba la diferencia fundamental entre el papel de China – que se ha desarrollado mediante su propia diligencia y perseverancia – y el de las potencias colonialistas/imperialistas, que construyeron su riqueza a partir del saqueo, el genocidio, el golpismo, el terror y la explotación. “China es grande, pero no es un Imperio. China no atropella a nadie, no ha invadido a nadie, no va por ahí lanzando bombas a diestro y siniestro.” El sucesor de Chávez, Nicolás Maduro, abundó en este punto: “Las relaciones internacionales de China parten de una base de igualdad, demostrando así que, en este comienzo del siglo XXI , es posible construir nuevas potencias mundiales sin la práctica imperialista de la colonización y la dominación.”

Venezuela ha sido receptora de extensas inversiones en infraestructura, y de grandes préstamos amistosos de China que han sido cruciales para sostener los programas sociales y los avances en el proceso de industrialización. Al pagar con petróleo a China (por una cantidad aproximada de 600,000 barriles al día), Venezuela puede seguir trabajando en pro de su objetivo de diversificación del comercio exterior. “Desde el 2001 Venezuela y China han firmado 480 acuerdos de cooperación y han participado en 143 proyectos conjuntos… Desde el 2005 al 2012 China prestó a Venezuela 47 mil millones de dólares, lo que equivale al 55% del crédito chino emitido a naciones sudamericanas en ese periodo.” La relación continua afianzándose, y la reciente visita a Venezuela de Xi Jinping produjo 38 nuevos acuerdos por un valor de 18 mil millones de dólares, incluyendo “un préstamo directo a Venezuela de 4 mil millones de dólares y otros 14 mil millones de dólares de financiación china para el desarrollo en proyectos de energía , minería, industria, tecnología, comunicaciones, transporte, vivienda y cultura” (ibídem).

La amistad con Rusia,

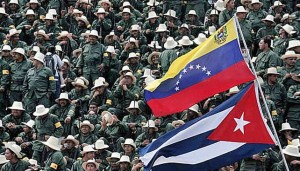

Por supuesto, las batallas para defender a Venezuela, para lograr integrar América Latina, y para construir un mundo multipolar no son sólo económicas o diplomáticas. La dominación militar preponderante de EE.UU. y de sus aliados requiere que las fuerzas anti-imperialistas sean capaces de defender sus logros con armas. Siendo el propio Chávez un militar, el Comandante nunca se cansó de afirmar que la Revolución venezolana es “pacífica, pero armada“. Si pensamos que en una amplia división del trabajo entre los constructores del mundo multipolar, China es la central motora económica, entonces Rusia tiene la iniciativa en las cuestiones militares.

Una nota necrológica en en la web Russia Today señalaba que, desde el 2005, “Venezuela adquirió armas de Rusia por valor de 4 mil millones de dólares, incluyendo 100,000 rifles Kalashnikof. Además, los dos países organizaron varios ejercicios navales conjuntos en el Mar Caribe. En el 2010, Chávez anunció que Rusia iba a construir la primera planta nuclear de Venezuela y que el país había suscrito otros contratos petrolíferos con Moscú por valor de 1600 millones de dólares.” Nicolás Maduro, entonces ministro de Asuntos exteriores, tenía muy clara las implicaciones de esta relación de su país con Rusia: “El mundo unipolar está colapsando y despareciendo en todas sus facetas, y la alianza con Rusia es parte de ese esfuerzo para construir el mundo multipolar.”

Una nota necrológica en en la web Russia Today señalaba que, desde el 2005, “Venezuela adquirió armas de Rusia por valor de 4 mil millones de dólares, incluyendo 100,000 rifles Kalashnikof. Además, los dos países organizaron varios ejercicios navales conjuntos en el Mar Caribe. En el 2010, Chávez anunció que Rusia iba a construir la primera planta nuclear de Venezuela y que el país había suscrito otros contratos petrolíferos con Moscú por valor de 1600 millones de dólares.” Nicolás Maduro, entonces ministro de Asuntos exteriores, tenía muy clara las implicaciones de esta relación de su país con Rusia: “El mundo unipolar está colapsando y despareciendo en todas sus facetas, y la alianza con Rusia es parte de ese esfuerzo para construir el mundo multipolar.”

Tras la compra a Rusia de una partida de misiles tierra-aire S300 en el 2009, Chávez declaró de forma contundente: “Con estos cohetes va a serle muy difícil a los aviones extranjeros venir a bombardearnos.” Visto el trágico destino de Libia solo dos años después, seria difícil aducir que el presidente de Venezuela sufría de paranoia.

A lo largo de la última década, el progresivo alineamiento de Rusia con el Sur Global ha supuesto un gran impulso para las fuerzas de la multipolaridad y del anti-imperialismo, especialmente cuando se compara con los oscuros días del clientelismo del bufón Yeltsin. Rusia ha aceptado este papel con aplomo, reconociendo que la continuidad de su independencia y de su desarrollo está estrechamente ligada al éxito de China, de África, y de América Latina. Algunos aseguran que Vladimir Putin le dijo a Chávez que su reelección en el 2012 fue “el mejor regalo que me podían haber hecho en mi 60 cumpleaños”. Unos meses después del fallecimiento del comandante Chávez, Nicolás Maduro presidió la ceremonia de dedicatoria de una calle de Moscú a Hugo Chávez Frías.

Avance en nombre de Hugo Chávez

La inoportuna muerte de este brillante ser humano fue un duro golpe para la humanidad progresista y deja un vacío que será muy difícil de llenar. Uno debe evitar caer en la adoración de héroes y la versión individualizada de la historia al estilo Hollywood, pero no se puede negar que ciertas personas, por su resolución, su comprensión, su determinación, su heroísmo, sus dotes de liderazgo, su genio creativo, su carisma, su devoción por el pueblo, desempeñan un papel destacado.

Hugo Chávez era así. Trabajó sin pausa en la consecución de su visión: por una Venezuela socialista; por una Latinoamérica unida y soberana; y por un orden mundial justo y multipolar, libre del dominio imperialista. Su visión era contagiosa y sirvió para inspirar a personas de todas partes del planeta. Dio vida a un proceso revolucionario global que se había manifestado muy poco desde el auge de la década de 1970 (Mozambique, Angola, Chile (1970-73), Guinea Bissau, Afganistán, Zimbabwe). En el período transcurrido fuimos testigos del declive y caída del “Bloque del este”, el surgimiento de economías neoliberales, la difusión del “ajuste estructural”, el impacto genocida del VIH/Sida y de una profunda desilusión entre la mayoría de la izquierda. La Revolución bolivariana, combinada con el ascenso de China y un mundo multipolar emergente, ha devuelto la esperanza.

Hugo Chávez era así. Trabajó sin pausa en la consecución de su visión: por una Venezuela socialista; por una Latinoamérica unida y soberana; y por un orden mundial justo y multipolar, libre del dominio imperialista. Su visión era contagiosa y sirvió para inspirar a personas de todas partes del planeta. Dio vida a un proceso revolucionario global que se había manifestado muy poco desde el auge de la década de 1970 (Mozambique, Angola, Chile (1970-73), Guinea Bissau, Afganistán, Zimbabwe). En el período transcurrido fuimos testigos del declive y caída del “Bloque del este”, el surgimiento de economías neoliberales, la difusión del “ajuste estructural”, el impacto genocida del VIH/Sida y de una profunda desilusión entre la mayoría de la izquierda. La Revolución bolivariana, combinada con el ascenso de China y un mundo multipolar emergente, ha devuelto la esperanza.

Hablando recientemente en el Museo Histórico 26 Julio en Santiago de Cuba, Xi Jinping afirmó que: “Los mártires revolucionarios son tesoros espirituales preciados que nos han inspirado a continuar avanzando.” Que el trabajo, ejemplo e ideas de Hugo Chávez continúen inspirándonos y educándonos, y que su internacionalismo revolucionario siga siendo estudiado y respetado.